Theatre history, like the theatre practice, aggregates across disciplinary boundaries. Each theatrical reconstruction involves excavating multiple sources: physical artifacts, spoken text, voices, gestures, designs, and audience response. Some of this cannot be recovered. Nevertheless historians assemble what they find and construct meaning around it. In this process, the computer functions as a tool for identifying and assembling information. Libraries and universities generally use static catalog-style listings to retrieve and display research materials even though post-millennial students, familiar with iPhone and iPad apps, prefer visual and tactile technologies. My hope is to encourage the use of dynamic technologies in theatre history research.

This year I am working with a team of undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Michigan with backgrounds in history, informatics, art and design, and theatre. Collectively we are developing a prototype web-based, interactive tool called 19thcenturyacts. The goal is to create an interesting and interactive visualization to track the life, travels, performances, cultural context and repertoire of the nineteenth-century actor Ira Aldridge as a prototype for other nineteenth century biography projects. Aldridge is one of the most documented African American performers who lived prior to the digital age. His global excursions epitomize African American cultural fluency during the nineteenth century.

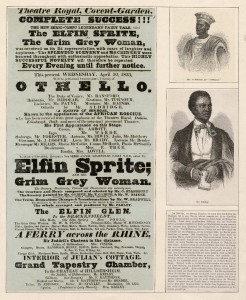

Playbill from Aldridge’s performance at Covent Garden, 1833 <http://digproj.libraries.uc.edu:8180/luna/servlet/s/s4g1g9>

Performance histories of non-western or working class people tend to be misrepresented within, or absent from mainstream archives. Paul Conway posits “In the Age of Google non-digital content does not exist, and digital content with no impact is unlikely to survive[i].” Preservation of digital content depends upon funding sources and some projects, usually works by “great” dramatists (Shakespeare, Ibsen, Chekhov), receive more resources. In this rush to digitize the familiar are non-textual or ethnic pre-twentieth century performances excluded from the archive?

One would hope not. As I reverse my thinking I can see that the Internet and its social networks encourage local communities to develop unique archives of crowd sourced, culturally specific materials. A jarocho music aficionado can, through blogs and user-networks, collect and disseminate digital materials that document performance practices within specialized interest groups. Accessing and redistributing in-group materials digitally merges archiving and distribution needs. Practices of crowdsourcing a performance history for ethnic performance hold possibilities for an ongoing, dynamic archive of non-mainstream theatrics. Such an archive of un-vetted resources, while broad in scope, may also consist of repeated visual motifs only marginally connected to original historical referents.

Recently, in support of a class lecture, I initiated a YouTube search for the nineteenth century dancer Juba thinking I would find documentary or media reconstructions of Master Henry Lane or John Diamond or perhaps the folkloric dance “Juba” attributed to the African American trickster character of Juba. Instead, YouTube provided links to rehearsals of a British tap dancer named Master Juba, a clip from the musical Stormy Weather, harmonic riffs by blues musician Guy Davis, and field footage of a dance festival in the Southern Sudan. These performance snippets document a historical archive of Juba simulacra far removed from a point of historical origin. While the visual documents may indeed belong in a collection of Juba-esque materials, they are quite removed from the original referent. Is there a scholarly collection of performance documents as vividly evocative or universally accessible as the YouTube site? I think not.

My “call” is for universities, museums and libraries to develop dynamic visual tools that make information accessible in interactive ways, and to provide context for crowd sourced digital data about the theatre. A fire hose of digital information inundates us. Without human mediation the overload of data creates a nonsensical cacophony. Are there new possibilities for editing within crowd source systems or within computer generated semantic technologies? Responsible custody of performance history demands that archives respond to widespread digital sources, including media and audio materials. If institutions are able to collect, collate, curate and then display data in dynamic and easily accessible formats then users and preservationist will both benefit.

[i] Conway, P. (2010). “Preservation in the Age of Google: Digitization, Digital Preservation, and Dilemmas.” The Library Quarterly 80 (1): 61-79.

{ 0 comments }