My recent research and writing on the poet Jay Wright has challenged me to go back to the Ancient Greeks a lot lately. Phrases like this one show up and send me on wild journeys through the classical texts: μὲν βάσις ὰγλαἴας ὰρχά.

I was starting to do so much work with Ancient Greek that I decided to purchase a subscription to the Loeb Classics Online Library, and to encourage my use of this amazing resource I started a blog series called “Classical Bellyflop.” The name comes from the feeling of leaping or diving into the classical texts curated in that library. Since my knowledge of Ancient Greek and Latin is pretty basic, however, any dive would scarcely resemble something pretty; not even a cannonball or a jack-knife would serve as an adequate comparison. No, when I dive into Ancient Greece I most certainly bellyflop. The text-water slaps me with as much force as my dive carries with it. The discoveries I make in the text are usually eye-opening and sometimes startling, similar to the surprisingly painful sensation of breaking the water’s surface.

I ended the last post (on repetition) with a consideration of the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves and the repetition that undergirds that telling, a repetition that is desired, actively tended, and yet also potentially upsetting. This entry you are reading here continues with this line of thought by questioning the ubiquitous use of the word “story” in the realm of social media. So many sites have a section for “your story.” The word shows up in so many places that its history has been evacuated. What does ”story” mean here?

The least generous reading of “story” in this context leads to an equation with marketing. When we update our story, we are marketing ourselves as products in the social marketplace. We market ourselves because we want someone to notice us, to listen to us, to engage with us. That desire is understandable and often sincere, but, at least on social media, it is necessarily bound up within “the society of the spectacle.” Fungibility overwrites intimacy. Our story is a transaction.

A more generous reading acknowledges that many of us—though certainly not all—are aware of the superficial dimension to this story telling, but we do it anyway. We tell “our story” because we want to feature highlights in the grand narrative that is our life. Still, though, a type of blindness persists here, one that becomes sensible through a question: are we in the story or are we making it? It often seems as though we would like to play out our lives as characters in a story that is written by some unseen author. Why? Simply put, it would be easier this way. It would be easier to play a predefined part, to enact a subject position or identity that is already created and in search of an operator or conductor. If we act in this way, however, if we accede to the fiction that we’re all stars in our own movies, then we forget the craft of making, the art of not simply telling a story but selecting one of infinite plots through which that story might unfold. If we think we’re only in the movie, then the ποίησις (poiesis) of life is by default ceded to another entity.

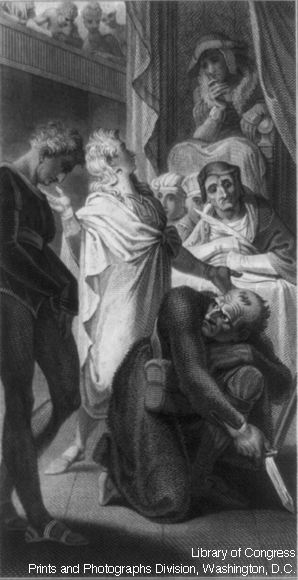

I’d like to suggest that, instead of blindly following the seductive marketing of the “story,” we focus more on the art of making. Furthermore, I would like to argue that we can do this by shifting our attention from our “story” to our “plot.” As I have said in almost every theatre class I have ever taught, plot and story are not the same thing. The story is like the wide-angle view of the events and characters that comprise any tale. The plot, by contrast, is the on-the-ground route that moves audience members and spectators through the story as it’s told. The ability to tell the same story by means of a different plot is what allows artists and entertainers to revisit the same stories from the past continually without losing the interest of contemporary audiences. For example, Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood is a re-plotting of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. The story is (generally, we are encouraged to think,) the same, but the telling is Kurosawa’s own. The route he plots through Macbeth is linked to his particular philosophy of cinema and his cultural milieux. We can’t discuss Throne of Blood without talking about Macbeth, but the story is not the most important part of Kurosawa’s cinematic event. The way he plots the story is a key reason why his film is so gripping and unforgettable.

To get to plot, though, it helps to go through “story,” which, for the Ancient Greeks, appeared primarily in two words: λόγος and μῦθος. The first, logos, was a foundational word within Ancient Greek culture. It meant “speech” and “reason.” To speak Greek was to move toward Reason. In the sense I’m referencing it here, however, the speech of logos is particularly a story or a telling of some event. The second word, mythos, which we also rely upon frequently in contemporary English (as “myth”), was a particular kind of story. It did not, as we tend to think today, denote a fictional story, but, rather, a founding story. The myth was an originating event, a happening that was so significant that it required constant revisiting (repetition) through the act of telling (i.e., rhapsodizing). The one who tells such a story is both a rhapsode and a mythologer.

There is no denying that story, as both logos and mythos, was important to the Greeks. Homeric Epics, for example, were myths that compelled constant retelling. When theatre rose to prominence and began to exert such a powerful role in (Athenian) cultural production, however, plot unseated story. At least, that’s what Aristotle leads us to think in his Poetics where, as Gerald Else tells it, he outlines the most important aspects of the art of making (and, in particular, the art of making tragedies). Of all the important aspects, plot is the most important. Reflecting on this today, it seems like this is the case because the telling of the story (myth) is what affected the course of ethical action in contemporary society, and, as such, a poor telling could literally pollute the city. A good telling was, by contrast, akin to the perfect path paved across a treacherous mountain pass. It guided the walker through the dangerous terrain to the other side of the mountain.

This word, however, “plot,” was not strictly equal with contemporary understandings of that word. Aristotle’s word was σύστασις (sustasis or systasis). When we look that word up in Ancient Greek dictionaries, we find that its definition as “plot of a drama” was far from primary. Its other definitions and usages included:

- bringing together, introduction, recommendation

- communication between a man and a god

- protection

- standing together, close combat, conflict

- meeting, accumulation, e.g. of humours

- knot of men assembled

- political union

- friendship or alliance

- composition, structure, constitution of a person or a thing

- coming into existence, formation

Looking at the list, it is possible to see how it comes to relate to the elements of a story’s structure, but this takes some work. To plot a story, we can deduce, is to bring together its most important elements so as to make visible the story’s lesson for the spectator. This, in fact, was theatre’s reason for existence. Theatre, the seeing place, the site where foundational lessons were plotted for use in the contemporary polis.

When we search for σύστασις in the Loeb Classical Library, we find again that the topic of literature is by no means the primary home for the word. In Aristotle’s other works, for instance, we find the following:

- Parva Naturalia. On Respiration: refers to “the constitution of the animal” and the “constitution of the organ,” meaning the way the working parts of an animal or vital organ are put together

- Meterologica: he speaks of the “formation” of a halo around the sun or moon; the “composition” of fiery, meteoric phenomena; the “collection” of vapor that forms morning dew; the “consistency” of a cloud.

- Generation of Animals: a reference to the substance “constituting” menstrual fluid; the “generation” of plants; the “composition” of the human body; etc.

- On the Heavens: the “coming together” of the parts of a human or of the world

As these examples suggest, the word that becomes “plot” in the Poetics surfaces in other works given over more to what we would call today the physical sciences. Likewise, it shows up in a similar usage in Galen’s On the Constitution of the Art of Medicine, Theophrastus’ On Odours, Plutarch’s consideration of the face that appears on the surface of the moon, and many other works. Is it at all strange, then, that Aristotle uses the word in ΠΕΡΙ ΠΟΙΗΤΙΚΗΣ, On Poetics, his discussion of the art of making tragedies? That he not only uses the word systasis but that he identifies it as the most important element of this art?

No, not when we consider how Aristotle’s disposition allowed him to look upon the art of making tragedy with the same eyes as he looked at the composition of animals. Aristotle was, after all, a man for whom the interplay of parts and whole, genus and species, was of the utmost importance. His concern with the “coming together of parts” so as to tell a story, therefore, makes sense. Likewise, his other keyword “catharsis” frequently carried the medical sense of “purging,” which was transferred to the work of tragedy: tragedy purged society of its pity and fear. Systasis and catharsis show how theatre, medicine, physics, and philosophy were all intertwined in Ancient Greece.

In my consideration here, the emphasis placed on “plot” by Aristotle deserves our attention because it shifts our thinking from the emphasis on “what” is being told to “how” it is being told. It also drags us out of the story and places us in a perspective from which we can view the making of the story. Both of these shifts are crucially important because they help us remember that we are makers. If we fall into the story and forget about the outside (i.e., the other people and animals and plants and objects and things that make the world), then we become players in someone else’s plot.

The “what” of a theatrical piece is the material, the “how” is the totality of decisions made by the artistic team to help an audience grapple with the material of a given show. In terms of our “stories,” the biography we write with our daily living, we tend to place a lot of importance on the “what,” on the material aspects of our life. On social media, many stories seek to show this material in a good light to anyone who wants to look. But the “how” of our story, the way we compose ourselves over time, is something much harder to showcase. This “how” isn’t visible in a snapshot or even a string of images over a short span of time. Speaking philosophically, the grand “How” comes together in its full form only once the story is over, that is, only once our life has been lived.

So what do we do about this? How do we shift from story to plot? The answer lies in ποίησις, the making, the construction of the story. We cause a disturbance in the society of the spectacle when we reveal how stories are made. This is the shift from History (the story of the past) to historiographies (the writings of these stories). Emphasize the way you make yourself. Show how you put your pieces together. Doing this forces us outside of the stories we tend to tell ourselves (repeatedly) about ourselves and challenges us to put things together differently.

Bio:

Will Daddario is the author of Baroque, Venice, Theatre, Philosophy. His current scholarly project is a book-length study of Jay Wright’s poetry, philosophy, and dramatic literature, co-authored with Matthew Goulish. In the realm of academia, he is currently most active as a member of the Performance Philosophy network (performancephilosophy.org) where he co-edits the Performance Philosophy journal and the Book Series.